Once again, thank you John, for sharing your story with us.

==========================================

INTRODUCTION

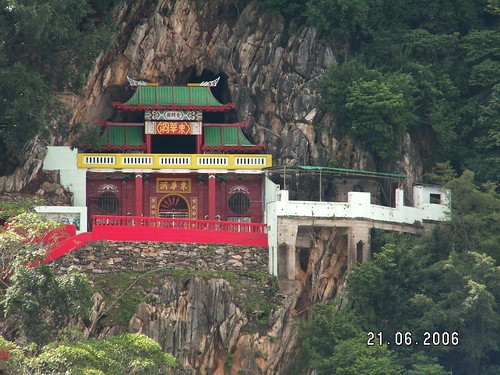

Following the surrender of the Japanese at the end of World War II, the military bases of Singapore were re-occupied by the commonwealth countries of Britain, New Zealand and Australia. During the 1950s and 1960s, many service families were posted to Singapore. Some of that time related to the communist emergency in Malaya, and spanned the granting of independence to Malaya (Merdeka) and the granting of independence to Singapore.

This series of articles looks at this period through the reminiscences of people who were schoolchildren of Armed Services parents posted to Singapore during that time. They lived in Singapore during a time of colonial occupation in what on reflection, was like living in an island paradise. During my own time there, my father's favourite song was Harry Belafonte's "Island In The Sun", playing it on the juke box in the Milk Bar in Changi Village whenever we went there (about once a month, so it was bearable). That love of the island was also very strong in a large number of the children.

LEAVING THE UK - INOCULATIONS, PACKING, SAYING GOODBYE

For many, this was a hectic time. You received the information booklet about Singapore giving you a load of information about the country with do's and don'ts which made interesting reading, but in no way could it fully prepare you for what you were going to experience. For many, the trauma of injections and inoculations was to follow. The TABT injection against typhoid was particularly painful. Many have described the painful swollen arm. For our family, the timing of the injections meant that the second injection was given on the ship as we sailed for Singapore. My younger brothers were given an adult dose through a miscalculation by the Army doctor on the ship and ended up bed ridden for a few days unable to move.

As service families, you usually didn't have many possessions, being ready to move sometimes at extremely short notice. However, there were items of clothing and some personal belongings to be packed. Some for storage whilst abroad and some to go with you to Singapore. Many children would see their toys going into storage for the duration of the stay abroad. Some toys were even given away! But this was often offset by the anticipation of moving to somewhere very different.

A pupil going abroad was a teaching opportunity for many teachers. Out would come the atlas and a look at the world map to show how far away the pupil was going. I think that to many people back in those days, where many people travelled no further than the coast for a seaside holiday, it was impossible to comprehend what a long journey it was going to be. This was particularly true for those travelling by ship and even more so when the ships had to go round the Cape at the time of the Suez crisis. Even the journey by air took more several days, compare that with the 11-hour journey of today between Heathrow and Singapore.

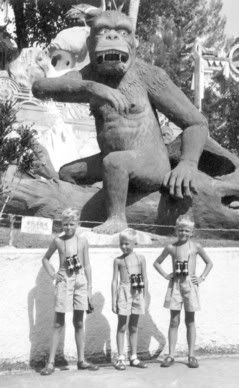

The year was 1957. We had lived in Cleveleys near Blackpool for nearly five years whilst my father was posted to RAF Weeton and it had almost felt as though we were putting down permanent roots. It was sometime just before my tenth birthday. My mother gathered my brothers Tom, Bob and me together one weekend when my father had got home from working Saturday morning and my father announced that he had been posted to Singapore and that we would be following him out there a couple of months after he was going. My father was a man of few words and left my mother to go through the booklet on Singapore with us. She explained where it was, beyond India but not as far as China and near the equator, the small diamond shaped island that looks like it is about to be swallowed by the snake head of Malaya. It was going to be warm but the air would be very moist and there would be quite a lot of rain. Later I read that booklet from cover to cover for myself and although I can't remember much of what was in there, I do remember thinking what a different exciting sort of place it seemed to be. After my father left, the next few months were going to prove a very trying time for my mother. She had to manage the packing up of everything we owned after sorting what was to come with us and what was to go into storage.

There were injections and inoculations, some of them very painful. We had to travel from Cleveleys to RAF Weeton for the Yellow fever injection but the rest could be done by our local GP. On the way for the smallpox inoculation at the local GPs, my brother Tom tripped over a kerbstone and broke his elbow. So as well as coping with the injection, he had to cope with the pain of a broken elbow. The doctor advised putting his arm in a sling and waiting until the morning before going to Victoria hospital to get it x-rayed and seen to. So that was the following day taken away from my mother's preparations to move. As the arm had swollen overnight, it wasn't put into plaster and he arrived home with it bound to his chest in a tight sling with lots of padding around the elbow. The preparations continued, friends and teachers were told of our forthcoming move, I don't think that most of them could comprehend moving half way round the world to another country.

At last brother Tom's arm was given the all clear and brought back into full use just two weeks before we were leaving. Unfortunately this wasn't to be the last disaster before we moved. A week later, I was playing cricket in the school yard at lunchtime. A ball came past me and I gave chase only to bump into somebody who turned round just as I got up speed, head down following the ball. Over I went with a sickening crunch landed on my wrist, sustaining a green stick fracture to my left wrist. I knew it was broken from the pain and the strange bowed appearance that looked like the broken right wrist I had sustained about eighteen months before piggy back fighting in the same school yard. One of the dinner ladies took me home and insisted that she take me on to the hospital so that mum could get on with the final preparations for moving. So mum gladly but nonetheless feeling slightly guilty, wrote a letter of authority for the dinner lady to act in loco-parentis and off we went on the tram to Blackpool to the Victoria hospital.

The letter proved useful as of course permission for me to have the bone set under anaesthetic was necessary. Coming back on the tram with my arm in plaster I suddenly felt sick and had to leave the tram for some fresh air. We walked one stop along and then got on the next tram that came.

THE JOURNEY

At last leaving day arrived. The two old ladies across the road came over to say goodbye and gave us a large bar of chocolate for the journey. We felt a little bit guilty as we had always called them the "mad ladies" because they had complained when we had lost balls in their garden. Many of the neighbours came to say goodbye and we were pleasantly surprised to see how many people had turned out just to say goodbye to us. We went to one of the Blackpool stations (I think it was the central one) and got on a train and eventually ended up in London where we were then taken by bus to the Union Jack club for an overnight stay. Next day after lunch we were taken to Waterloo station and put on a boat train to Southampton. We shared the train compartment with a Glaswegian family and although it was difficult to understand what they were saying at first, my ears tuned in after a while and life stories were swapped. As the train arrived my mother got me to put a Macintosh over my arm to hide the plaster, as she wasn't sure whether we would be allowed to travel if anyone spotted it. To make doubly sure my brothers and the Glaswegian family we were sharing the train carriage with surrounded me to further hide the arm.

Before us was what looked to me like a magnificent liner, the S.S. Dilwara of the B+I line. I had never been this close to such a large ship before. (You can see a photo of the S.S. Dilwara here) Trawlers in Fleetwood harbour and steamers on Lake Windermere had been the largest things that I had seen. After our documentation had been checked, we all trooped up the gangway with all the children still crowding round me to hide the arm in plaster. Once on board I was confined to the cabin until we had set sail and were well away from the port before I was allowed out of the cabin.

As it turned out, my mother's instincts had been correct as the M.O. said that I shouldn't have been allowed on board with my arm in plaster. Despite that, he did arrange for the plaster to be removed at an Army base when we arrived in Mauritius. Life on board a ship with your arm in plaster is an interesting experience as a young lad. At first I was a little bit cautious, but I quickly adjusted and almost became unaware that the arm was in plaster. I think that a few of us must have been just about all over that ship including areas that were marked out of bounds for passengers. It was great fun for a young lad, and we never got caught although it was a close call sometimes.

Meals on board were always signaled with a bell and there was always a great stampede to get to the dining room. Most children would be running and do a hurdle-style jump through the step of the bulkhead door leading into the dining room. In the Bay of Biscay, the ship was rolling quite violently from side to side, the bell rang and instinct took over with the usual rush amongst those that had good sea legs and were not confined to their cabin with seasickness. Leaping over the bulkhead step the ship rolled and the angle of the step came up to meet my trajectory and over I went completing my entry into the dining room with a sprawling somersault. Somehow I managed to hold my plaster cast arm out of the way and fortunately no damage was done. How nobody was ever hurt in that three times daily stampede I'll never understand.

We were soon out of the Bay of Biscay and heading to warmer latitudes. A couple of days each week, a part of the deck would be flooded as a shallow swimming pool cum paddling pool so that we could cool off. To make use of this my mother used to bind my plaster cast up in a plastic bag with sellotape. It was not particularly comfortable with the plastic bag and also trying to keep the plaster away from any inadvertent ingress of water but that cooling dip in the water was well worth it.

As we passed round Africa our first stop was in Dakar to take on fuel. I can't remember much about Dakar except that the stop was short and we didn't even leave the ship. The next stop was Cape Town where we were taken off the ship and went for a bus tour of Cape Town and Table Mountain. On returning to the ship mum bought some extremely large pears. Half a pear was enough and I swear they were the sweetest juiciest flavoursome pears that I have ever tasted. I'm drooling just thinking about the juice dribbling down my chin.

Malcolm and Ian Younger broke out in a rash, I can't remember whether it was measles or Chicken Pox, after a few days on the ship and were confined to a quarantine cabin situated near the back of the ship underneath the lifting gear. On nice days they were allowed to come out and look down enviously at the rest of us having fun. It wasn't until they got out of quarantine that we got to know them and found out why they were up there. We all thought that they must be an important family with a special cabin! Malcolm and I became fairly good friends during that time and at Changi we lived in the same road for some time and were in the same class at school. By chance as well, when we returned to the UK, the Younger family arrived back a few days after us and were staying in the same transit boarding house in Blackpool where we both attended Blackpool Grammar School in the same class again. We both hated that school with a vengeance, but that's another story.

From Cape Town we headed up into the Indian Ocean heading towards Mauritius which was to be our next stop. Part way there, a load of activity took place with removal of the hold covers and testing of the lifting gear. We had also changed direction. The Tannoy system boomed out that we were diverting to pick up an injured seaman from another ship who needed urgent medical attention. Half a day later it was announced that another ship had got there before us and that we would be returning to our previous course.

Arriving in Port Louis was an interesting event. The whole port area had an awful smell and we nicknamed it Port Pooey. The following morning I left the ship with my mother to be met by an Army ambulance on the dockside. We seemed to drive for hours and hours through mile after mile of sugar cane and up towards the mountains. I suspect that it was only about a half hour; it just seemed longer in the back of an ambulance with nothing to see except mile after mile of sugar cane. A recent visit to Mauritius has confirmed my memory of vast expanses of sugar cane.

The plaster cast was by now only loosely covering my arm which had shrunk with sweating and the muscles wasting away. When the M.O. got the snippers out to remove it, I told him there was no need and just slipped the cast off over my fingers. The arm was duly X rayed to confirm that the break had healed OK. Despite the healed bone, the M.O. said that he was not going to take a chance with a young lad traveling on a ship getting into mischief and re-breaking the arm. One of the biggest disappointments of lie was to have a new cast put on and then it was back into the ambulance and back to Port Louis and the ship. Arrangements were then made for the removal of the cast when we arrived in at RAF Changi in Singapore. In the meantime all the other children had been taken off to a beach somewhere for the day. For many years I felt jealous of my brothers Bob and Tom that they had been taken to a beach somewhere. I only found out a couple of months ago that the person who was looking after them whilst my mother and I went to have the plaster cast seen to, made them sit under the trees in the shade and wouldn't allow them to go anywhere near the water. Jealous feelings immediately extinguished. I probably had just as interesting a time of it as they had, even if was only looking at mile after mile of sugar cane.

From Mauritius to Singapore, time seemed to drag. I laid in my bunk at night hearing the persistent throb throb throb of the engines. Even watching the porpoise and flying fish had become boring - it was almost routine to look over the side to see if there were any fish or porpoise. It felt like we were trapped on the S.S. Dilwara and it was hardly moving with us never to see land again. It may not have been the Marie Celeste, too many people on board, but the slowness of that last part of the journey must come a close second to forever sailing round the world. The novelty of being on board a ship had worn thin and it was a great relief when we finally entered the Straits of Malacca and we could see land nearby. Suddenly the voyage had become exciting again with just one day to go. We made our way down the coast of Malaya overnight and docked in Singapore harbour in the morning. As the ship was docking I could see my father standing on the dockside, he looked different in Khaki Drill shorts, as I had only ever seen him in his UK Air Force Blue uniform. We disembarked and were led to a bus that then took us to the Tanah Merah Country Club where we were treated to a Coca Cola. This was my first taste of the drink and it was to become a firm favourite during our stay. Another favourite was the Sarsaparilla that they sold in the NAAFI. After the drink, it was back on to the bus and not long after, we arrived at Lloyd Leas married quarters. We had finally arrived after having set off from England six weeks before. Within a few days my plaster cast was removed and we could get down to the serious business of getting acclimatised and getting to know people. The broken arm disasters were not over yet. We had only been at Lloyd Leas a few weeks when my youngest brother Bob was outside playing when he fell over a dog and broke his arm. In those days my mother felt that her second home was the hospital. Despite the setbacks though, we were glad that we had arrived and were settled into a nice bungalow.